Does mob justice improve society?

In ancient Athens, Socrates was sentenced to death by a democratic jury for "corrupting the youth” and impiety. Essentially, he was canceled by his society for challenging dominant values and questioning authority. Citizens also voted once a year on whether to exile any one individual for ten years—no trial, just popular consensus.

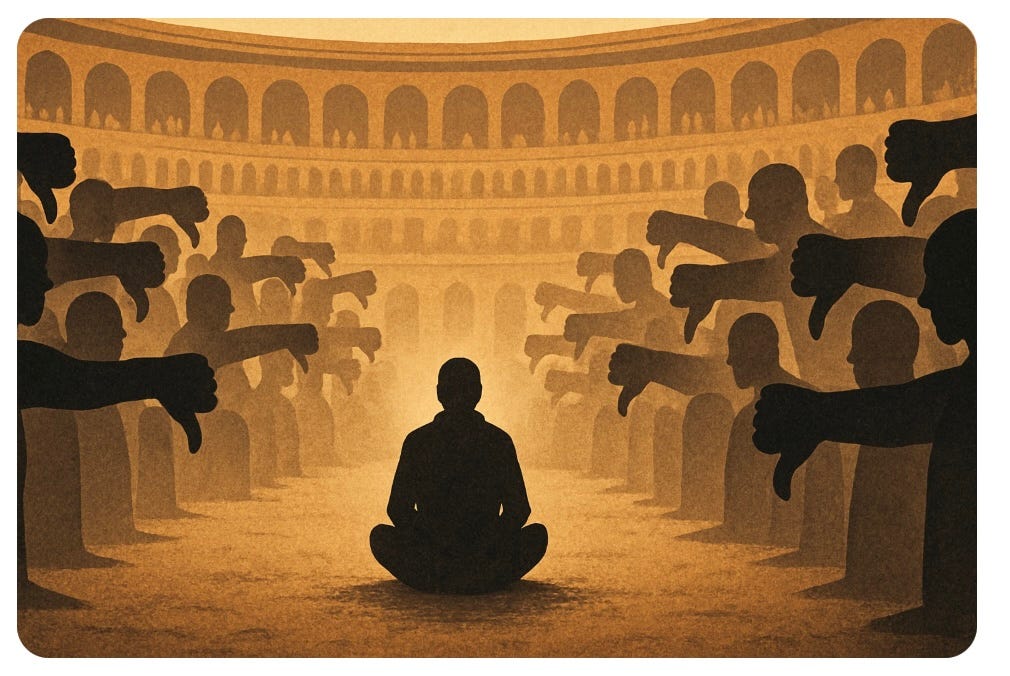

Although today, in the Western world, we have laws that don’t allow the execution of individuals for their views, nor do we force them into physical exile—in the court of public opinion, anything is subject to prosecution. Whether that’s a tweet from five years ago, a poorly chosen phrase, or an opinion that does not adhere to the orthodoxy. Whatever is considered outside the realm of the acceptable. Step on the wrong side, and the mob awaits. Some call it cancel culture, others…accountability.

And truly, it can be either. It is all part of the virtue economy. Crowdsourced justice.

At its core, mob justice is a bit like a ‘market correction.’ It identifies, exposes and punishes what’s considered by some to be immoral behavior or speech. It’s a moderating force that aims to restore virtue in society through shame, ostracization, as well as social and professional penalties, ensuring that there are consequences for the perpetrators. Moral correction through public scrutiny.

The process is by now predictable. First comes the exposure: a resurfaced tweet, or perhaps more current wrongthink. Then the public shaming begins. It comes of in the form of furious social media activities, complaints to employers, and even think pieces by media outlets (if there’s sufficient attention). The next step is distancing. Friends disappear and unfollow. Opportunities vanish. Social invitations withdrawn. In the final act, the subject is rendered unemployable, friendless, and unworthy of redemption. They are outside the bounds of the acceptable.

In some cases, this social exile has led to the ultimate loss: of life. Suicide is seen as the only exit clause for some.

If this sounds harsh, it is. The criminal justice system—flawed as it is—at least has an established set of rules for violations, due process, and proportionality of punishment for the crime. There’s even the possibility of parole. Both social courts and real ones can serve as a deterrent to poor behavior and that plays a critical function, but the public court of opinion has no formal appeals process, no statute of limitation, and there are no defense lawyers present to present the case of the abused to the jury.

The judge, jury, and executioners are the mobs, fuelled by moral puritanism. Mobs aren’t known for being wise or for practicing restraint.

This is where it gets complicated. Who decides which offenses are worth punishment? Seems like if a sufficient number of people believe you’ve transgressed, the consequences will be doled out, even if that group represents a very minor percentage of the overall population. How do we moderate the severity of the punishment and its length? Such a mechanism is not available. Why does one person face annihilation while another with a similar infraction is forgiven, or worse, ignored?

Many of those cancelled are not career thought criminals. Often they’ve just been blindsided by social rules that have shifted without notice. Unlike in court, “intent” is hardly ever considered. The level of public exposure, however, dictates the outcome.

When we put people in prison there are several intentions: deterrence, public safety, and eventual rehabilitation. But as anyone who’s done their time knows, life doesn’t suddenly become normal once you’re out. Aside from the adjustment, former felons often struggle finding housing and employment. They’ve paid their ‘debt to society’ but even though they are no longer in prison, often their sentence continues in a different way. And here we can draw a parallel.

How do the cancelled—whether former convicts or thought criminals—survive? If they cannot find employment, who foots the bill? Their families? Our taxes?

It is worth asking: do we seek correction or vengeance?

But does everyone really deserve a second chance? Certainly some criminals are handed lifetime sentences, so the answer appears to be no. It seems tougher to judge when the transgressions are more about words than actions.

If someone has accepted responsibility, should they continue to be punished? Can an apology really absolve them? What about those who never do acknowledge their part? Should we banish them? The powerful, in particular, can often escape justice. Some view ‘cancel culture’ as the only available tool by which simple people can hold those with power accountable. While someone like Harvey Weinstein was eventually taken to court, his unrevealing begun with a media story and a social media hashtag. Many more guilty parties could not face court, but the mechanism of social justice made them unable to hide their actions any longer. They evaded court, but became personas non-gratas. (Though, of course, importantly, some of those falsely or unfairly accused also suffered similar fates).

But the truth is that some people will never change, and their words/actions do matter—even if they don’t reach the criminal. Truly abhorrent behavior or speech can’t be entirely cost-free in a cohesive society. It’s just that we have such a hard time judging or moderating who should pay what.

In many cases, rather than resorting to punitive actions, it seems like honest and direct discourse would have a more positive outcome. When people are able to learn or rethink their actions, they have a chance to improve themselves and therefore make a more positive contribution to society itself.

When they are attacked, they tend to become defensive and dig in.

If the goal is moral evolution, wouldn’t education and engagement be the preferred first step rather than exile? We should acknowledge that sometimes even permanent exile from public life is indeed warranted, but it should be a last resort.

Like the criminal justice system, we should be focused on more than just punishment. We should offer an opportunity for growth and, at times, redemption and return.

‘Cancel culture’ sends a warning. And sometimes that warning is more than warranted. But it also, too often, gets things wrong. And delivering ‘mob justice’ tends to make people feel virtuous, which is a rather addictive feeling. But is that hit of dopamine worth the destruction of a person’s life? Or the societal impact of people being terrified of sharing their honest thoughts in case they step onto a landmine?

What’s ultimately at the heart of cancel culture isn’t always just some moral puritanism, vengefulness, or cruelty—it is a desire to have some control where traditional power structures often failed to deliver justice. It gives ordinary people a lever to demand consequences. It’s a sense that if enough voices join in, they can have power to make a change. And sometimes, that works. But this same tool can also destroy indiscriminately.

The challenge, then, is learning how to wield the power of collective outrage with discernment—without it hurting more than it heals. And that’s a much more complex task than many of us like to acknowledge.

☕️ You can support my work by sharing, subscribing, or making a one-off donation via Buy Me a Coffee.

Bravo; another excellent essay. One minor caveat would be to avoid confusing the intensity of the social media backlash with the number of people who support it. Social justice warriors are very good at inflating the attention they receive by using exaggeration, misinformation, and outright defamation to stoke public outrage.

In my opinion, more often than not, the outcomes are predicted by the actions (or failures to act) of administrations rather than characteristics of either the “victims” or their targets. Administrative failures to protect academic freedom and due process can be due to mere cowardly incompetence but sometimes reflect willful collaboration to eliminate those who question their authority or the party line.

There are many examples of this in Professors Speak Out; The truth about campus investigations. (Nicholas H. Wolfinger, Ed.) Washington, D.C.: Academica Press. For those interested, the Martin Center will be hosting an hour-long zoom session: Webinar Registration - Zoom Professors Speak Out; May 22 (4-5pm EDT).

Protect yourself at all times, call that an answer by one who survived an attempt on their life.

Eye for eye is the law of the jungle which is more prominent unfortunately it seems for specific nobodies.