The Vanishing of the Internet

I’m sure that you’ve heard the adage that the “Internet is forever” or “the Internet never forgets.” But as it turns out, that’s not quite true—unless, of course, you’re a celebrity who said the wrong thing on MySpace 15 years ago. Then, it sticks around forever.

According to Pew Research Center, 1 in 4 web pages that existed between 2013 and 2023 can no longer be accessed. That includes links to news stories, government pages (how will we track policy changes now?), and so on.

The vain human that I am, from time to time, I would Google myself—mostly to ensure that nothing overly strange or controversial would show up. Media outlets have a habit of randomly quoting my posts on social media. In the process, I had discovered that most of my journalistic work has vanished from the Internet. Or rather, it was no longer being indexed by Google, which, isn’t so different from a vanishing. Even if those published articles still exist, they cannot be found.

That discovery was alarming to me.

While it’s understandable that some websites will eventually have the plug pulled—like your old geocities masterpiece and ode to puzzle games—I worry that we are losing some valuable data too, factual, cultural and historical.

According to Pew, 38% of pages from 2013 are inaccessible today. More recent content is inaccessible at a lower rate, but it’s still high enough to be concerning. Clearly, the Internet is indeed…forgetting.

In the past, libraries served as repositories that documented our lives—including keeping records of past articles on microfilms and encyclopedias. But as we’ve gone digital, the amount of data has grown extremely vast—hundreds of billions of pages.

On the one hand, the Internet doesn’t require quite so much physical space to store data, but on the other, there’s no central entity tasked with safeguarding it.

Google has always had an algorithm that prioritized some pages over others. It was a necessity for prioritizing quality content and ensuring the end user didn’t have to sort through thousands or even millions of pages. But on what basis did they “disappear” content that had previously showed up at the top? Age? If so, then it’s a problem when we can no longer reference back to potentially rather pertinent information. The publications I had written for still exist.

But perhaps it’s not entirely Google’s decision. Simon Brew writes that some of this content is being scrapped to improve from Google’s search algorithms, which favor faster loading times and user experience. Older content often falls by the wayside, especially as publications update their CMS systems, orphaning past articles that are no longer compatible, choosing not invest the resources needed to preserve and transfer them over.

There are, of course, organizations that are attempting to archive as much as possible. Amongst them is archive.org, “The Wayback Machine,” which has kept snapshots of websites on particular dates since 1996. However, it is a non-profit, has limited resources, can only capture data on occasional dates, and we still end up losing a lot. It also requires a lot more digging to find old content. It was also recently hacked, defacing it, temporarily shutting it down, and impacting 31 million users with data breaches.

The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine preserves over 900 billion webpages, some of which have even been cited in court as evidence. Fortunately the data itself was left intact by the hackers, but things could have been worse.

A coordinated effort to ensure the preservation of digital history is needed. We must build more fortified systems to protect digital data, just as we preserve libraries and their archives. Perhaps not everything needs the same level of protection, but certainly important documents, government communications, and articles do. It’s essential when it comes to protecting our collective memory.

Then again, in the Stone Age, when cavemen carved out their drawings, perhaps they thought they’d last forever too. Some have, but many more are gone. And like those ancient carvings, the digital traces we leave today may one day crumble into obscurity, lost to the tides of technological change.

The Internet’s memory, too, is fragile. There’s too much content to “never forget.” That is, unless it’s an embarrassing tweet.

☕️ By popular request, you can also support my work by making a one-off donation via Buy Me a Coffee.

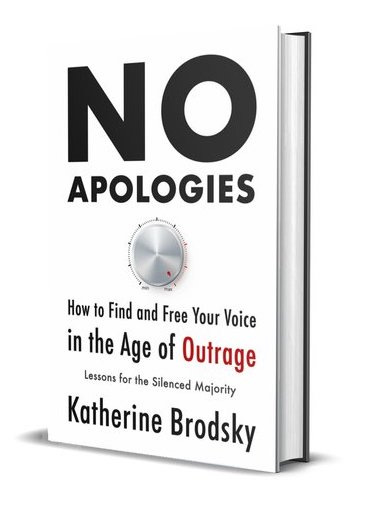

Order my book, No Apologies: How to Find and Free Your Voice in the Age of Outrage―Lessons for the Silenced Majority —speaking up today is more important than ever.

NOTE TO READERS:

Thank you for keeping me company. Although I try to make many posts public and available for free access, to ensure sustainability and future growth—if you can—please consider becoming a paid subscriber. The more paid subscribers I have, the more time I’ll have to work on new essays.

In addition to supporting my work, it will also give you access to an archive of member-only posts. And if you’re already a paid subscriber, THANK YOU!

I routinely suggest to people that they investigate Google alternatives. I pay a few bucks a month for https://Kagi.com, which has no ads, provides excellent search results, and has more useful features than Google, notably the ability to lower, raise, or outright block sites in future search results (so they can better reflect your own judgement of accuracy and relevance.) I suggest giving it a try for a month, including searching for your own past work.

I'd hazard a guess that it's not strictly google who have triggered the un-indexing but rather the sites hosting the content have chosen to update their robots.txt in response to AI learning and data scraping activities.

Many prominent sites like reddit have recently done this, much to the dismay of users who have relied on doing google searches for sites that have poor search functionality themselves and i suspect this is only going to get worse.. is going to be interesting to see how google try to maintain revenue from there bread n butter, AdSense, in the coming years as web searches become a thing of the past like altavista, lycos, yahoo etc did :)

And yeah yeah yahoo is still around but its not what it used to be just like myspace :P~

PS congrats on the 5000, i'd say i'm shocked it's not higher but in this clown world it's a testament you haven't been cancelled for simply talking with Musk yet! 🥰