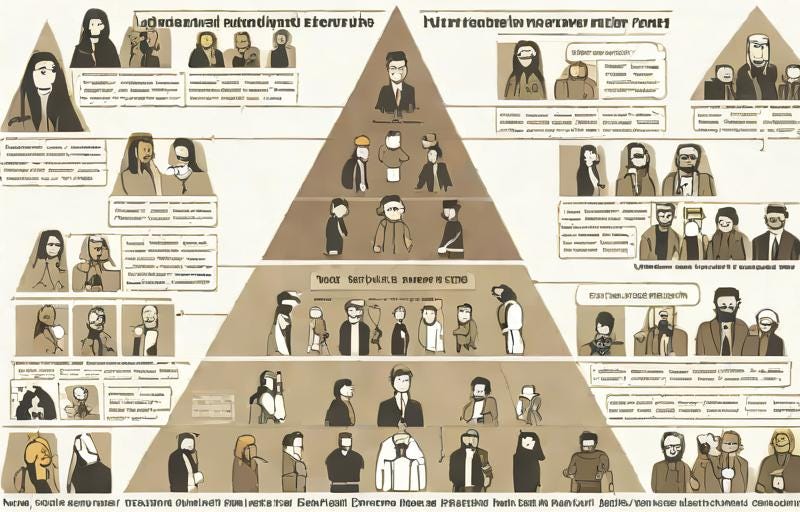

Victimhood Hierarchies

If you’re a woman, you’re more victimized and oppressed than a man. If you’re a Black man, you’re more oppressed than a white one, but possibly less privileged than a white woman.

If you’re an immigrant with a certain type of accent, you’re less privileged than someone with a different kind of accept. But if you’re a millionaire and an immigrant with an accent and a certain shade of skin color, you’re hard to place.

If you’re a trans woman, you’re more oppressed than a trans man, because passing for a man is a privilege. But if you’re a Black trans woman, you’re the most oppressed.

Forgive me if the math gets a little confusing.

But one has to wonder why we might bother evaluating the levels of victimhood or oppression in the first place? Does it help solve them?

Now, I’m not going to deny that we’re not all playing with loaded dice. Some of us are wealthier. Some of us are healthier. Some of us do indeed face more discrimination. That’s the reality of the world. While we should strive to live in a “colorblind” society, we clearly do not. While people shouldn’t be discriminated against based on their gender or sexuality, they clearly are. Frankly, while the problem is getting less significant in some parts of the world, I’m not convinced that it will ever fully disappear. Even if we all one day look exactly the same and be one gender, we’ll still find ways to divide ourselves and pit ourselves against each other. Such is the nature of humanity.

But, I have to ask, what problems are we solving by comparing each other’s suffering or challenges? Why isn’t it just enough to acknowledge them and seek to address them through education, empathy, laws, and so on?

What is the precise benefit of saying that one group or individual suffers less or more than the one next to them?

The answer seems to be “power.”

Why else would someone seek to view themselves as the MOST unfortunate if there was nothing to gain from that association? It’s kind of like saying “I’m the least popular kid in high school and I always get picked for teams last.” There’s something rather humiliating and disempowering about that. Unless it is supplemented with: “But I don’t care what others think and I still kick ass and look at everything I’m doing.”

These days, victimhood can be rather lucrative and doesn’t have to involve overcoming anything. It can be leveraged for power. Those who can cast themselves as victims are able to gain moral authority and sympathy, which can help shape opinions or gain support for a cause. Or sell books. Book media appearances. Or, I don’t know, shaming dinners (aka hazing rituals for white liberal women)? Guilt is a powerful motivation to have people part with their funds.

It also means that it’s an effective tool for mobilizing others, especially guilty-feeling parties, to support particular causes or policies. To be an “ally” one must also defer to perspectives of the oppressed. Some of it comes out of signaling obligations, but often from a genuine perception of guilt and duty. The way it can look is when, say, at a seminar, creative workshop or board meeting, some voices are prioritized over others purely due to their status to the exclusion of others. Media attention is also granted for that reason.

When it comes to resource allocation, policies are often designed not to just follow a hierarchy of needs or merits, but, victimhood and oppression. This means anything from access to grants to educational opportunities and awards.

The more someone is seeing as being higher on the victimhood hierarchy, the more they are able to benefit from these rewards. Allocating them not based on need, but based on perceived hierarchy—thus actually taking away from those who have genuine needs.

But it’s important to note that it’s not necessarily merely the “victim class” that encourages this. We see plenty of people attach themselves to this approach despite not being the direct beneficiaries.

Except, they are.

Some of it comes down to narcissism. It’s about signalling their own moral superiority and virtue by advocating for others. But they don’t do it for all group, they aim for the most oppressed groups because it’s essentially a competition with other “virtuous” people.

The irony is that often those same people will reinforce existing power dynamics, where they are placed higher, by claiming to care about these victim groups. (“See, I can take of you from my position on the ivory tower, like no one else. So I should stay there. You’re safe with me.”)

Political agendas can also come into play. Attaching themselves to certain people as victims can help advance their own interests, whether that’s gaining approval for a certain policy, getting votes from that group, or hurting opponents.

Now, I’m not saying that no one genuinely feels supportive of oppressed groups in any kind of altruistic way. Some are even willing to sacrifice their own standing, and have true empathy. And some of that is actually needed for change to happen, for policies and advocacy.

However, the comparisons leave a lot of room for victimhood not to merely be empathetically acknowledge and addressed, as it should be, but also manipulated and exaggerated for personal or collective gain.

The constant comparison can further perpetuate power imbalances and hinder genuine progress toward a more just and fair society. In fact, it often fosters division and resentment among various marginalized groups. When individuals or groups vie for the title of the most oppressed, it can lead to infighting and the prioritization of one group's needs over another's, undermining any collective efforts to address issues.

Instead of competing over who is more victimized, we are better served by acknowledging and working to correct systemic and societal issues for EVERYONE, so that we can create a more level playing field, whether people shine or flop.

Order my book, No Apologies: How to Find and Free Your Voice in the Age of Outrage―Lessons for the Silenced Majority —speaking up today is more important than ever.

One of the most fundamental tenets of social science is that differences within groups are usually greater than differences between groups. We have more in common than we realize, and this is just as true of oppression as it is of most other human experiences. One’s identity affects the likelihood and level of oppression they experience, but this piercing glimpse into the obvious is not the whole story. What are less obvious, but perhaps more important are the intra- and inter-personal personal factors which influence this phenomenon.

The survey study that cost me my job as a tenured professor provided some relevant findings: 1) respondents who agreed that it was appropriate to shout down a speaker whose message might be hurtful to others; 2) identified as “extremely liberal;” or 3) agreed that protection from hostile environment discrimination was important, were more likely to perceive a hypothetical scenario as being a “hostile environment.” They also judged that the words or behaviors that created the situation would not be protected by academic freedom. https://researchers.one/articles/22.11.00007v1

More recently, a study by Lahtinen reported in the Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, identified many beliefs closely related to critical social justice (i.e., wokeness) Construction and validation of a scale for assessing critical social justice attitudes ttps://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/sjop.13018

Even more interesting, was his finding that the more of these beliefs an individual endorsed, the greater the likelihood that they would suffer from anxiety and depression. The gist of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is to identify and dispute the stupid (and oppressive) things we tell ourselves. As Albert Ellis might have said, there is nothing more oppressive than our own ”stinkin’ thinkin’.

Katherine,

I think "colorblind" is not the best word to describe what you (and Coleman Hughes) are advocating. Just as I could not be blind to the fact that you're a woman, I could not be blind to someone's skin color or the weather at the moment (raining and grey in NYC).

What do I have to offer as an alternative? Admittedly, nothing great at the moment. But it's worthwhile considering if there's a better way to say it.